A Gateway Through Gateway: Coordinated Entry in Atlanta

- Christopher Rosselot

- Mar 29, 2023

- 3 min read

Public policy is confusing. And that’s coming from me—a student who spends his day in the policy world. How, exactly, do government programs work? And, maybe more importantly, why do they work the way they do?

At The Backpack Project, we operate in the space of housing and homelessness policy. Yet, with our organization being run by students, we would be hard-pressed to tell you how or why federal, state, and local homelessness policy functions in its current state. We certainly do not need policy expertise for what we do, but we do need to know how our governments say a community should come together to support those experiencing homelessness.

On Friday, January 20, we took a trip with four of TBP Athens’ Directors to the Gateway Center in Atlanta. Anyone who works in this space will tell you the Gateway Center is the rock of Atlanta’s homelessness assistance policy—everyone passes through their doors, specifically the doors of 275 Pryor St., Gateway’s primary location. This is not just hyperbolic—the Gateway Center is Atlanta’s designee for Coordinated Entry.

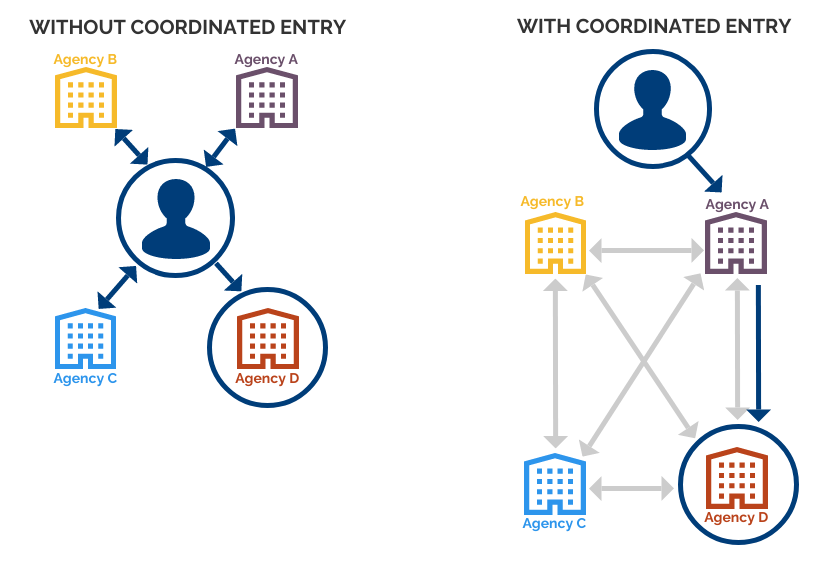

Coordinated Entry is a standardized process in which those seeking assistance enter a singular agency, undergo a screening, and are assigned to case management at any number of agencies working in the broader regional umbrella of service providers. That umbrella is called the Continuum of Care (CoC)—Georgia has 9 CoCs, one each in Atlanta, Cobb, DeKalb, and Fulton. The CoC applies for and receives federal funding, which is allocated to member entities (like Gateway).

Whew. Complicated already. But the system is logical and orderly... right? Drew Benton of Gateway showed us how this system functions well in some regards and could use some tweaking in others.

Let’s take the Coordinate Entry intake process as one example. 1.5 (1 full-time and 1 part-time) Gateway employees lead the Coordinated Entry process each day. Folks start lining up at 7 am at Gateway’s doors because, according to Drew, only 10 units (individuals or families) can be processed in a singular day. As for those not in the first 10? They’ll have to try again. This means coming back day after day at 7 am—and figuring out an alternative solution in the meantime.

Next comes the Vulnerability Index - Service Prioritization Decision Assessment Tool (VI SPDAT). The VI SPDAT ranks individuals seeking assistance in accordance with risk factors where those with higher scores (i.e. “riskier”) are pushed towards more intensive support and case management. Certainly logical—but also cold and calculating, in my opinion. After a client completes the intake process, they are often reassigned to another agency. Faces change as you no longer see the outreach worker or the intake employee with whom you’ve started to connect.

But, at the Gateway Center, we did see those supportive faces. We heard about the Upward residential program Drew facilitates, where 20 men receive support in job searching, addiction recovery, and so much more. We heard about the Engagement Center where public showers and hygiene kits are available. We walked through Mercy Care’s adjoining clinical space where doctors and nurses can see patients. And this is just a small, small sample of what takes place.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway for me from our time with Drew and the folks at Gateway is this: systems can never be perfect. People? Well, we’re already so imperfect that as long as we keep trying to connect to each other, we might just find community.

DAFTAR AKUN VIP ACEH4D

DAFTAR AKUN VIP ACEH4D

DAFTAR AKUN VIP ACEH4D

DAFTAR AKUN VIP ACEH4D

DAFTAR SLOT GACOR

DAFTAR SLOT GACOR

DAFTAR SLOT GACOR

LINK ALTERNATIF

LINK ALTERNATIF

LINK ALTERNATIF

DAFTAR ACEH4D

DAFTAR ACEH4D

DAFTAR ACEH4D

DAFTAR ACEH4D

SLOT GACOR

SLOT GACOR

acehbola

situs slot dana

BANDAR TOGEL ONLINE

toto togel

slot online

acehbola

situs bola online

Situs Bola Online

situs slot dana

Situs Slot Dana

Situs Mix Parlay

acehbola

situs slot toto

situs judi bola

Situs bola Online

slot gacor

situs slot online

situs bola terbaik

aceh4d

aceh4d

aceh4d

situs togel